Welcome to Liturgical Threads! Today, you will find notes and thoughts on the Epistle reading. The Hebrew Bible reading ran earlier this week; the Gospel reading will be coming later this week. Thank you for reading!

Grace and peace,

Justin

Philippians 3:4b-14

If someone else thinks they have reasons to put confidence in the flesh, I have more: 5 circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; in regard to the law, a Pharisee; 6 as for zeal, persecuting the church; as for righteousness based on the law, faultless.

7 But whatever were gains to me I now consider loss for the sake of Christ. 8 What is more, I consider everything a loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whose sake I have lost all things. I consider them garbage, that I may gain Christ 9 and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which is through faith in Christ—the righteousness that comes from God on the basis of faith. 10 I want to know Christ—yes, to know the power of his resurrection and participation in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, 11 and so, somehow, attaining to the resurrection from the dead.

12 Not that I have already obtained all this, or have already arrived at my goal, but I press on to take hold of that for which Christ Jesus took hold of me. 13 Brothers and sisters, I do not consider myself yet to have taken hold of it. But one thing I do: Forgetting what is behind and straining toward what is ahead, 14 I press on toward the goal to win the prize for which God has called me heavenward in Christ Jesus.

The past is an alluring thing.

We can see that all around us, in the cultural obsessions roiling our body politic. Nostalgia is one of the things at the root of the MAGA phenomenon; Donald Trump's whole thing is "Make American Great Again", a promise of a return to something in the past.

So, too, is the resistance movement to him in 2025: we want a return, to a quieter yesterday when democracy was respected and our political fights were about health care and Dodd-Frank and No Child Left Behind. We want to fix our politics in a way that undoes the last decade we've all lived through.

Every one is looking for a better future by recreating what we imagine to be a better past.

Its a natural thing, especially for politics. A political or ideological program is simply the creation of a vision of the way the world can be - and what better place to draw upon for that vision than the past. The danger comes when we forget that our remembrance of the past is flawed, and partial, and selective. When we forget the parts of our past that weren't so rosy as we attempt to pattern our lives on that past, we create gaps in our vision. Those gaps are what bad actors seek out, and where they thrive. Those gaps are where the brokenness is, like cracks in a foundation, undermining the whole structure.

The apostle Paul was in the business of projecting a vision, of how the world could be. This vision, crucially, was not based on a past that he was attempting to recreate. A new world, was what Paul was after, centered on the coming of Christ, projected in the future. The past was the foundation being built upon, but it was not the goal or the pattern. "What I am doing," he writes, "is forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead."

Paul does this in spite of all the past had been for him. He was well-known, highly regarded, successful, a paragon of what it meant to be a Pharisee. "If anyone else has reason to be more confident in the flesh, I have more", he boasts, listing all the ways the world had been his oyster:

"I was circumcised on the eighth day.

I am from the people of Israel and the tribe of Benjamin.

I am a Hebrew of the Hebrews.

With respect to observing the Law, I'm a Pharisee.

With respect to devotion to the faith, I harassed the church.

With respect to righteousness, under the Law, I'm blameless."

And yet, all that is but loss, he says now. Living into a new way of being, a way conformed to the life of Christ, Paul has given up those shackles of the past, for something new. Just like Jesus, of who it is said,

"Though he was in the form of God,

he did not consider being equal with god something to exploit.

But emptied himself

by taking the form of a slave

and by becoming like human beings.

When he found himself in the form of a human,

he humbled himself be becoming obedient to the point of death, even on a cross."

Imitation of Christ is the life we are called to.

Not a recreation of the past.

Not an ideology.

Not a political platform, or a party line.

Kenosis: a self-emptying, of all that we have been, and all that we are, and all that we are anxious to be. Empty ourselves, like God did.

In his new book, Jesus Changes Everything, theologian Stanley Hauerwas writes,

"Followers of Jesus, therefore, are not concerned with anxious, self-serving questions about what we are able to do or what we ought to do to make history come out right. In Christ, God has already made history come out right."

Instead of an anxious grasping after some pre-determined system of fixing the world's ills, we are called to some more life-giving than that. "Jesus doesn't teach a new law or depict some impossible idea. He describes what life is like when God's kingdom breaks into our midst." We are called simply to hear what the Good News, and then to live like it is true. We can empty ourselves of our pasts, of our anxieties, of our plans and programs and ideologies, and just live.

Let other people run the rat race, wield power, try to fill the hole in their being with the need to dominate others. On that way leads emptiness.

Instead, turn the other cheek.

Go the extra mile.

Consider it all a loss, and rejoice.

In humility, and lowering, and weakness, find God.

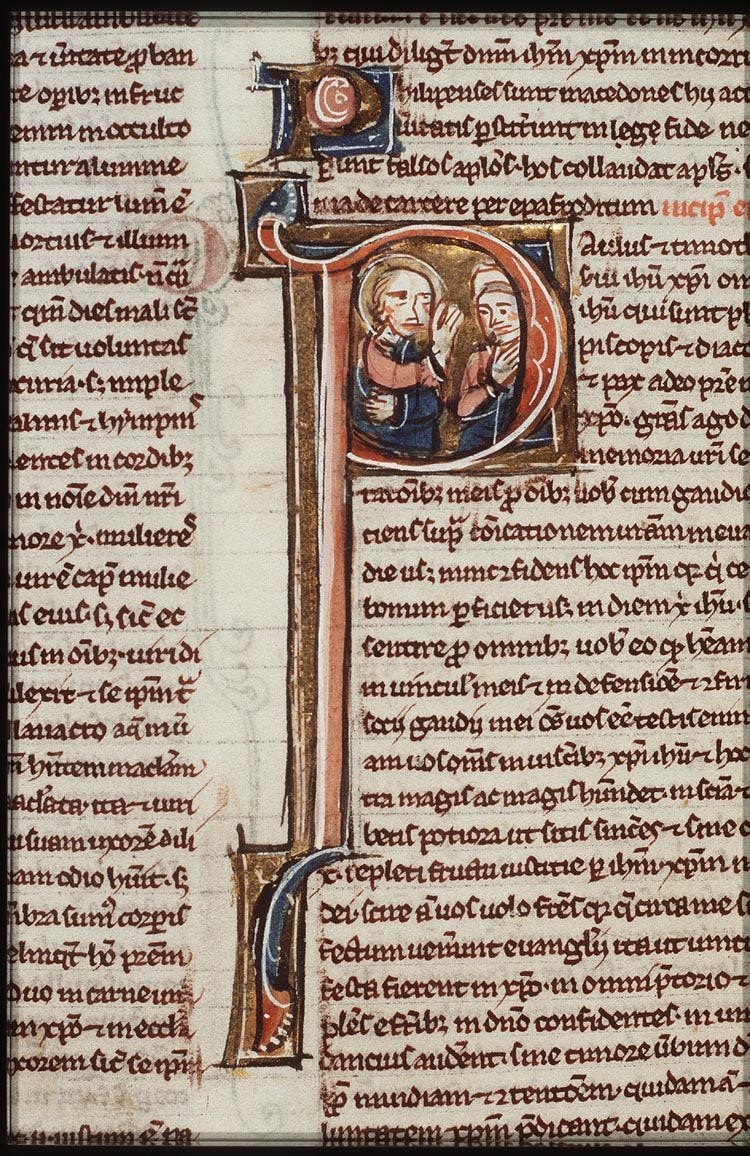

The letter to the Philippians is one of the seven undisputed letters of Paul, written by the Apostle while he was imprisoned, likely to the house church centered on the home of Lydia. Acts chapter 16 relates Paul's mission to the city, which was located Macedonia, on the Aegean coast.

Philippi was a relatively young city at the time of Paul's visit and writing. Founded as a colony of Roman soldiers by the emperor Augustus less than 50 years earlier, Philippi had been notable as the location of the battle where Augustus and Mark Antony defeated the assassins of Julius Caesar, driving Brutus to suicide. The city was thus important to the cult of Augustus, as well as an important stopping off point on the Via Egnatia, a major east-west route connecting the Roman world to the East.

All this combined to make Philippi a bustling imperial metropolis, home to a variety of temples dedicated to all manner of deities - and also home to a wealthy woman, Lydia, described by Acts as a dealer in purple cloth. Lydia would become an important benefactor of Paul after his visit and imprisonment in the city, and as an independent merchant, was likely one of the richest women in the city, and it is probably that the house church meeting in the city met in her home or place of business.

Paul's letter to the church at Philippi has as its centerpiece one of the most striking and important passages in the New Testament: the Christ hymn of 2:6-11. Likely written well before Paul was converted, the hymn showcases some of the earliest liturgical emphases we have, as well as sheds some light on the early Christological features of the faith. New Testament scholar Michael Gorman describes Philippians as "an extended meditation on, or exegesis of, the Christ hymn." Going on, Gorman writes, "Paul composes a letter that relates the story of Christ narrated in 2:6-11 to the ongoing story of the Philippian community."1

The hymn introduces the key Christological concept of *kenosis,* a Greek term referring the idea of the "self-emptying" of Christ on Cross, and consequently, of God as well. As the hymn says, Christ "emptied himself, taking on the form of a slave, being born in human likeness", despite his own divinity. So too, Paul writes in today's reading, followers of Christ, living in imitation of Him, should empty themselves of all their worldly accomplishments and trappings, and seek to the "sharing of his sufferings by becoming like him in his death." Paul even relates all he gave up as a prominent Jewish scholar and religious figure for the sake of following Christ.

All this kenosis has a purpose, Paul writes in the last two verses of today's reading: pressing on towards the goal of eternal union with God, in Christ. Paul frames this in athletic terms, comparing his hearers to runners in a foot race, urging them not to look back at what came before, but to keep their eyes forward, on the goal.

Reflections

Use for private meditation or journaling, or feel free to use these as prompts in the comments below.

What would kenosis look like in your life?

What do you think Paul means when he calls his previous achievements “a loss for the sake of Christ”?

Thinking politically, what would it mean to try to mesh the political predilection for making plans and programs with the Christian imperative to put aside anxieties and to stop trying to make history come out right? Are these two things compatible, or inevitably at odds? Is there a way to expand our political imaginations to encompass such an attitude?

Gorman, Michael J. Apostle of the Crucified God: A Theological Introduction to Paul and His Letters, page 419. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, 2004.